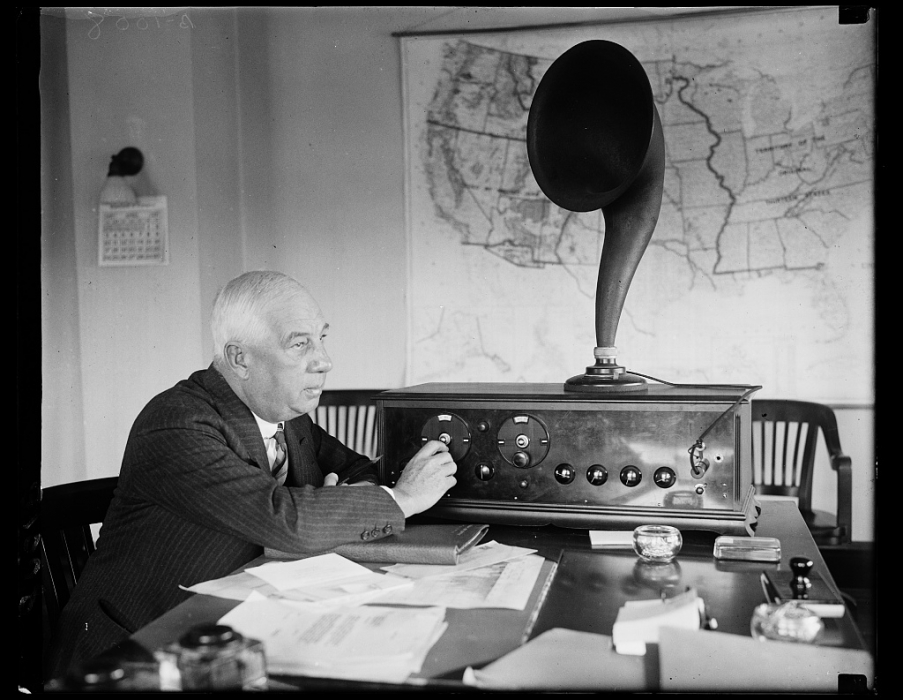

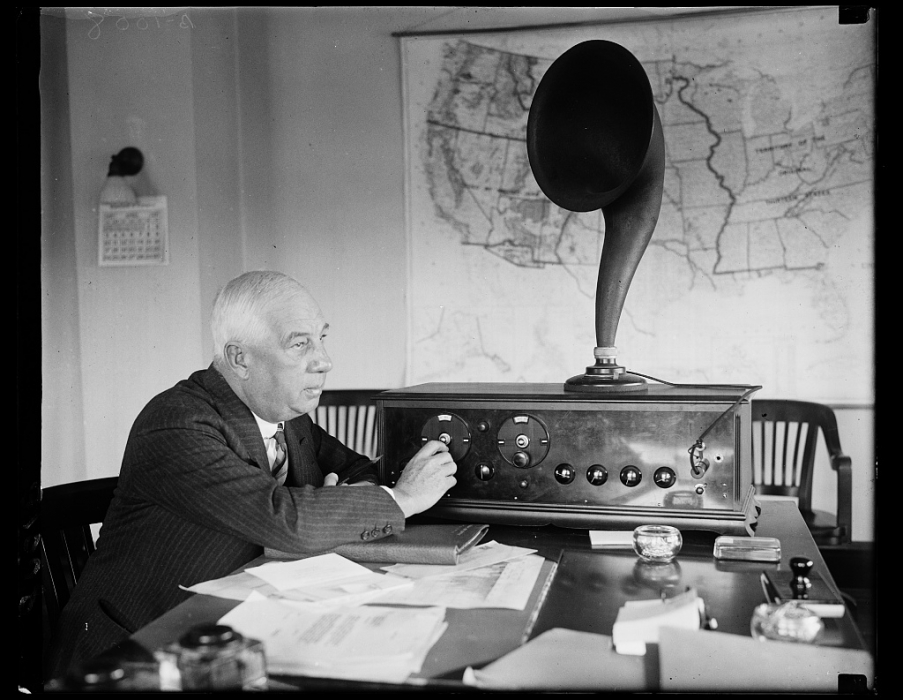

Rear Admiral W.H.G. Bullard, chairman of the newly created Federal Radio Board, "tunes in" on a radio set in his office at the Department of Commerce on April 14, 1927. The new radio commission was created by the Radio Act of 1927 to license broadcasters and reduce radio interference. (Photo via Library of Congress, public domain.)

The Radio Act of 1927, which superseded the Radio Act of 1912, was signed by President Calvin Coolidge on February 23, 1927.

The act created the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), which was primarily directed to license broadcasters and reduce radio interference, a benefit to both broadcasters and the public in the chaos that developed in the aftermath of the breakdown of earlier wireless radio acts. One assumption underlying the act was that the First Amendment protected radio as a form of expression.

There were several other underlying assumptions:

Section 18 of the Radio Act of 1927 was a forerunner of the equal time rule by ordering stations to give equal opportunities to political candidates.

The act did not authorize the Federal Radio Commission to make any rules about advertising. However, it forbade programming that used “obscene, indecent, or profane language.” Otherwise, anything could be programmed. The act did vest in the Federal Radio Commission the power to revoke licenses and give fines for violations.

Because the broadcast industry was concerned that the government’s licensing power might degenerate into censorship, Section 29 of the act, while prohibiting obscene, indecent, or profane language, provided that the commission would not otherwise have the power to censor the content of programs.

The concept that broadcasting was a privilege was not considered a violation of broadcasters’ First Amendment rights. The radio industry generally accepted the premise that “free speech” did not mean the right for anyone to say anything on the air. Free speech issues in 1927 were secondary to ending the airwaves chaos.

In 1934 Congress replaced the Federal Radio Commission with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Radio Act of 1927 with the Communications Act of 1934.

This article was originally published in 2009. Sharon L. Morrison was the Library Director at Southeastern Oklahoma State University.